In case you missed Part I of the series, I started with the backbone of what I believe is a good strategy creation process. Namely, the way of working of the leadership team.

In part II of the series I talk about the two ways to create and continue to evolve strategy. On y va….

What is Strategy? (Besides an overly misused term in business, that is🫠). Officially, by definition in the dictionary: “Strategy is a plan of action designed to achieve a long-term or overall aim.” I am not a fan of this definition because it conflates the ‘direction’ you take, with the ‘plan’ for execution. I think they are two different things (think of the debate over the Richard Rumelt structured way to create strategy, vs. the Henry Mintzberg emergent way), and for the purposes of this discussion, I want to focus on the direction, not the plan. Good strategy results in a plan (i.e. how you will get there). But it starts with a direction (i.e. where do you need to get to).

I prefer Roger Martin’s definition, because it focuses on the direction:

In business, Strategy is about making an integrated set of choices that positions you on a specific plane, compelling a desired customer action.

That’s the direction. What’s the end state of the customer and company. The plan would be, what’s the roadmap for delivery, the sequence of events that you need to take to “make” these choices.

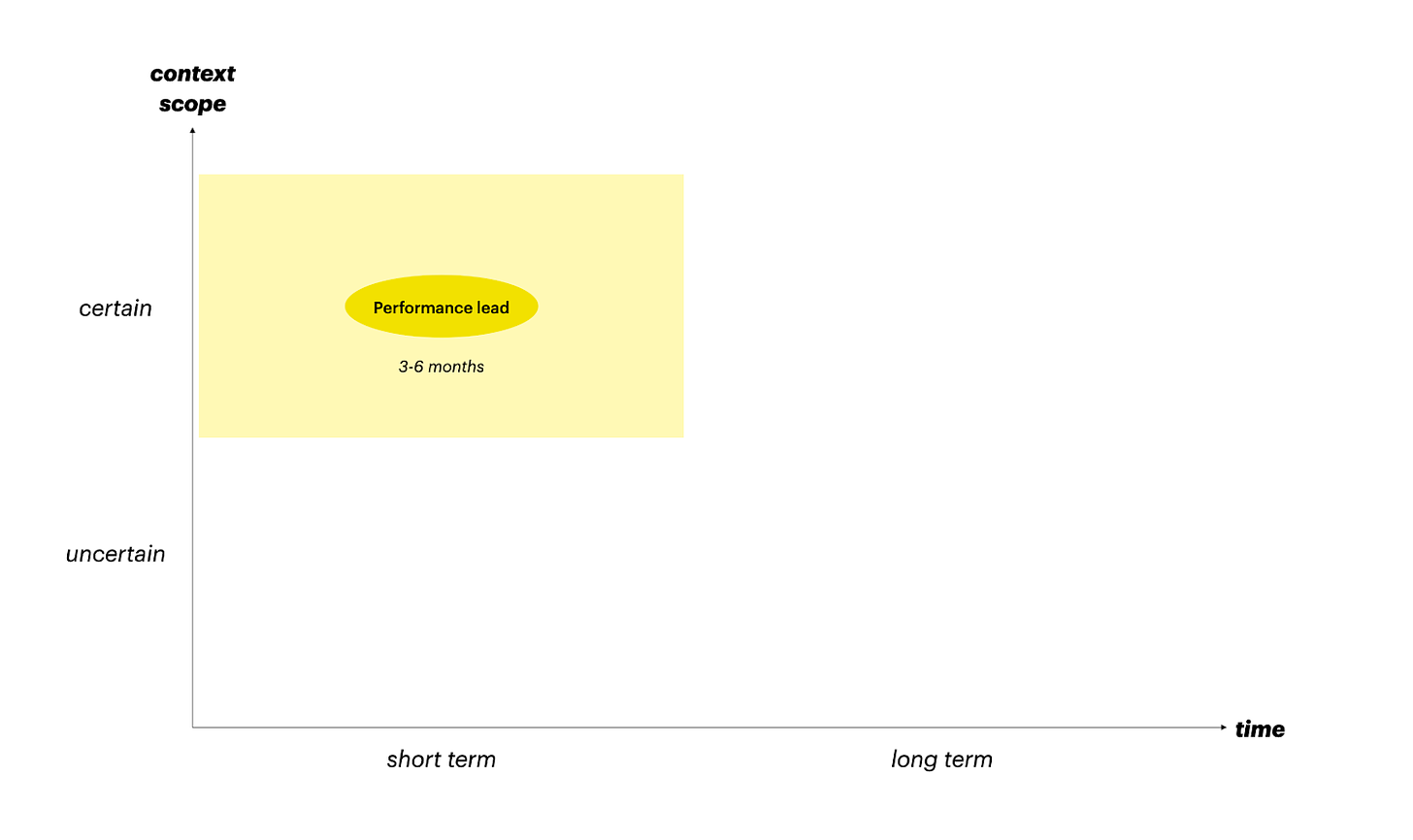

There are two things that matter when setting a direction:

Context Scope: how certain or uncertain the direction’ input information is.

Starts with the data: is it widely available, or do you have to make assumptions? If you have to make assumptions, what is your degree of confidence? Imagine the different information available to a B2B company with 10s of customers, where you’d fight for new data. Now imagine a data-rich company, with 100s of thousands of users, like Uber, where you have to choose the data you use.

Then the history: have you been operating for 1 year or 10 years? Or maybe the company has been around for 3 years but is launching a new motion? Or a new product? Imagine a start up trying to define its PMF. Now imagine a Figma, launching a Figjam.

Then the learnings: do you operate with a level of predictability, where you know how much X will move Y? Or do you operate from a blank slate? Imagine a young company still setting up its systems to obtain insights. Or a Revolut changing pricing slightly.

And last but not least the way of working: what (and who) do you need to take along in the decision-making and story? Think about a founder-led approach where one or two people carry the weight of the vision. Now think about a company where you need to gather the expertise of local GMs to determine the “correct approach” and ensure their buy-in.

Time Scale: when do you expect to see an effect of your strategy? Or, what is the time scale of scale?

If you have PMF, or a very clear demand/segment fit? That’s short-term. Or if you see rapid growth emerging from a market and you decide to capitalise on it? That’s also short-term. Your focus is on PMF, in some shape or form.

If you need to “create a category”, or educate specific segments? Now that’s long-term. Or if you need to reach a new type of customer, and you need to build a Partner ecosystem in a specific region, which would take 3-5 years? Long-term. This is when your focus shifts to scaling out for years to come.

Based on the context scope, and timescale of ambition for the future, I see two points of view in crafting strategy. Let me first illustrate with an example:

#1 Performance-lead: this is how Uber does it for its local markets: Strategy/Ops Managers gather the data (and Uber has lots of data!), then they discern the patterns, build a picture, tie it into the growth plans, and recommend a 3-6 months path for execution. GMs want to see growth, but it is within a predictable range. It is what I did, leading UberExec/Lux. You combine research of existing ride patterns, rider perceptions, driver needs, legal requirements, operational opportunities, GTM avenues, and add some magic & math => a strategy.

#2 Vision-lead: this is how early stage start-ups do it: start with the vision about where the market is going and what the company’s place in that world is, who do you want to serve, and how, and add some magic & assumptions => a strategy. It is a top-down decision-making process, ideally based on an objective perception of where customers are and how they want to buy, now vs the future.

Your job as a strategist in #1 is to craft a clear, analytical, and actionable story for predictable growth. And in #2 is to set a visionary outlook, flexible to be adapted to market changes and opportunities. You are playing different games. Each type attracts different people, and works at different levels, even!

If you are reading between the lines, you will already see some differences between the two. Let’s look in detail:

Performance lead

Performance lead strategy has a more certain context scope. This means it is based on robust data, where you can discern what to optimise for, and where the decisions for the strategy can be executed by a diverse base of the workforce. And as such the focus is its success over the short term. A few key characteristics:

Data - it is based on robust data analysis, and (internal and external market) data is available and reliable. The company relies on such insight to make decisions. Assumptions exist, but are commonly agreed upon, and carry minimal risk to the company.

Legacy - sets clear objectives in line with a long term vision. Always asks “how is this initiative contributing to the overarching company strategy.” It is based on learnings from outcomes achieved in the past.

Predictability - it is carefully planned and executed. It involves implementing a systematic process, enablement, and measurement to achieve goals, and obtain new learnings.

Bottom up - this approach engages a broad range of stakeholders in the strategy formation process. Involving various perspectives leads to deeper insight, and a thought-through and resilient strategy.

Performance-lead strategies are an excellent tool in data-rich, established environments where short-term optimisation is crucial.

Vision lead

Vision-lead strategy has a more uncertain context scope - this is because the future is uncertain. It is based on assumptions about the future state of the world, can neglect the history of a company in favour of what it could be, and is typically driven by a few individuals that set the tone. And as such the focus is a bet over the long term. A few key characteristics:

Assumptions - whether leaders are aware, this approach is based on assumptions about the future state of the world, the macroeconomy, the trends in customer needs and behaviour, growth rates, the capabilities and ROI of technologies and so on. The company relies on such foresight to make decisions.

Vision - this approach calls for a crystal clear vision about who you are building for, what you are building and the type of world you are building. You can disregard past performance if you are planning on a complete overhaul of what ‘was’ and want to focus on what ‘will be’.

Optimism - planning and executing a plan is less important that having a ‘can do’ attitude, and rolling with the punches. With high uncertainty, the ability to capture opportunistic value is paramount, as long as it fits with the vision, and the cost/benefit analysis doesn’t show financial, regulatory, or culture risk to the company.

Top down - this approach maintains a coherent direction and aligns the organization around common goals. It is typically led by one or few individuals, who the company trusts to have the foresight into what the future might hold.

Vision-lead strategies are an excellent tool for uncertain, rapidly evolving markets where long-term transformation is the goal.

The Yearly Strategy approach

Well designed yearly strategy plans combine the two approaches. Depending on a company’s performance, stage, and leadership’s desire for change, each point of view will weigh differently. Furthermore, in one company, you might see a mix of approaches for various departments, products, or initiatives. John Cutler refers to these as the Bet Portfolios. Here are two examples of what the end state of the yearly plan looks like:

The more risk-taking the company, the more Vision-lead the approach is. Founders have little data, they want to change the world, the past doesn’t matter, and they are optimistic about the future. They feel that they can break (or significantly change) past performance to dictate the future.

The more established the company, the more Performance-lead approach weights. After all, if it ain’t broken don’t fix it, so managers rely on proven paths, rather than innovative (i.e. risky) initiatives based on their intuition. Unless there is a perceptible need for change in the next year, in this scenario, you’d stick to your guns.

As we've explored, strategy isn't a one-size-fits-all concept. It's a dynamic interplay between the choice you can make and customer action, shaped by your context and time scale. Whether you lean towards a Performance-lead or Vision-lead approach, the key is to align your strategy with your company's unique situation, goals, and risk tolerance. Most successful companies blend these approaches in their yearly planning, adapting the balance as needed, on company and initiative level.

As you evolve your strategy, consider these questions:

Where does your company (or initiative?) fall on the Context Scope and Time Scale dimensions?

How can you leverage your data and experience while still remaining open to transformative ideas?

What's the right balance between performance optimisation and visionary thinking for your current business stage?

Ultimately, effective strategy is about making informed choices that drive desired customer actions. By understanding these different approaches, you're better equipped to craft a strategy that not only responds to your current reality but also shapes your company's future.

Comments and questions are welcome, through the usual channel: LinkedIn message.

Post word:

you will notice I left the bottom left bit of the 2x2 untouched. It is on purpose. This is where I typically put rapid experimentation that stress tests assumptions, and bring new learnings. Anything you’d put in the bottom left corner of the 2x2 is experiments, testing, and research.